Kaare Klint

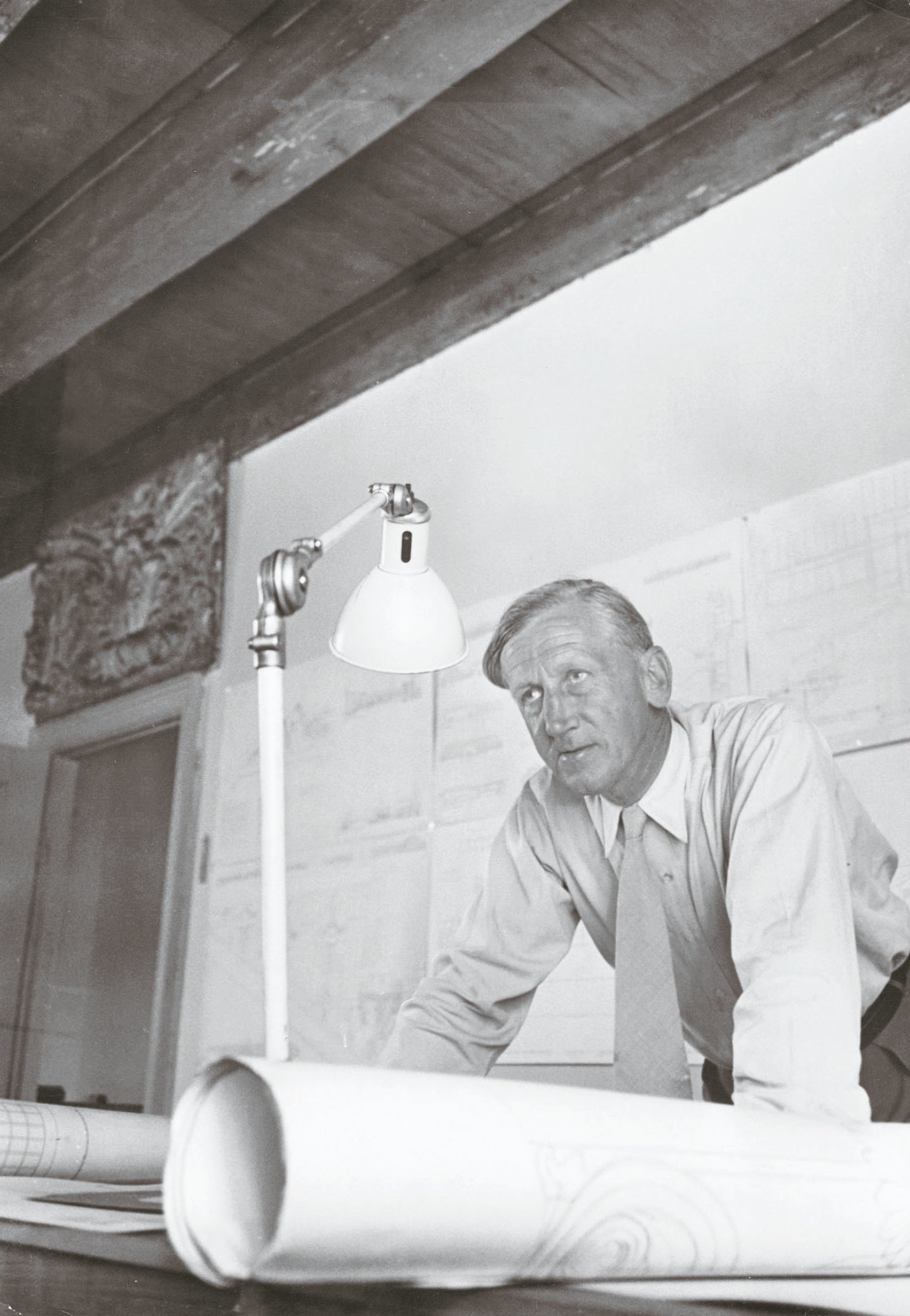

Architect, furniture designer and visual artist, 1888 - 1954

Kaare Klint was an architect, furniture designer and visual artist and was the brother of Tage Klint, who founded the lamp company Le Klint in 1943.

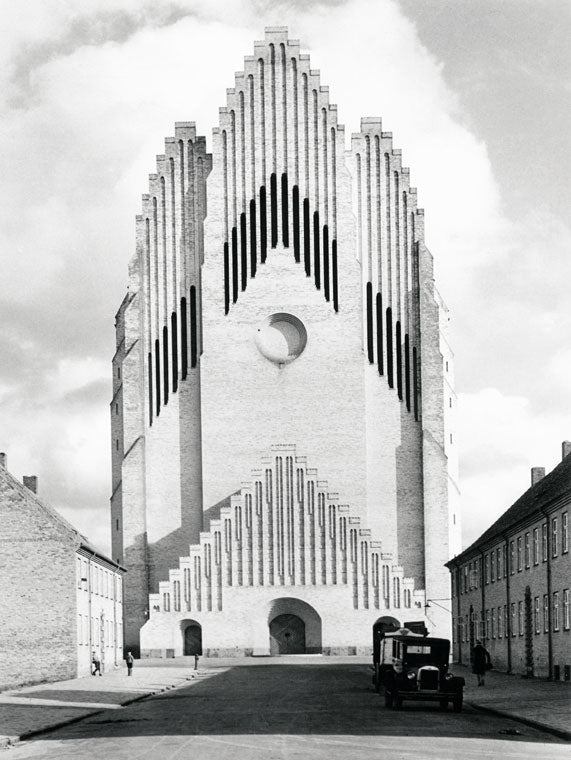

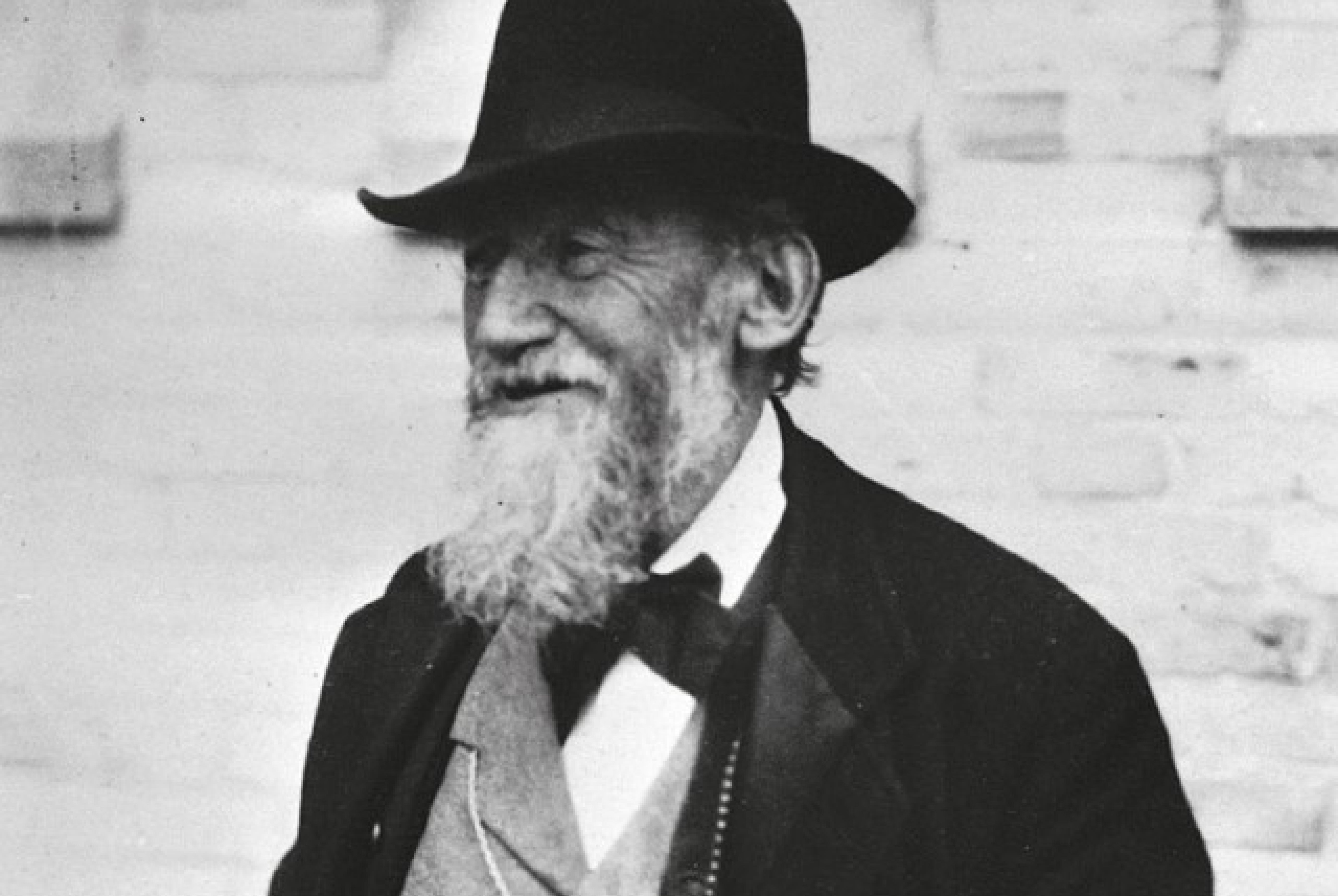

He was an apprentice of his father, the architect behind Grundtvig's Church, P.V. Jensen Klint and of the architect Carl Peterson, from whom he learned the Danish tradition of classic realism, as seen in Abildgaard and Bindesbøll. In order to produce furniture with the right dimensions, Klint took an interest in the measurements and movements of the human body. In 1923, Klint gained employment at the School of Furniture Design at the Academy of Fine Arts. In 1924 he became a lecturer and in 1944 he became a professor of architecture.

A great influence upon Danish furniture design

Through his own furniture designs and his teachings, he influenced an entire generation of Danish furniture designers. He emphasized good materials and perfect craftsmanlike manufacturing. He thus had a particularly close collaboration with Rud. Rasmussens Snedkeri (Rud. Rasmussen's Cabinetmakers, now Carl Hansen & Søn), which still produce a wide range of his classic furniture.

The Faaborg, safari and church chairs

His best known furnishing designs include: The Faaborg chair, or "karmstolen" (sill chair) for Faaborg Museum in 1914, the Safari chair of 1933 and the Church chair with woven sea grass (French weave). It was designed in 1930 for the Bethlehem church in Copenhagen, which was the first Danish church to try using rows of chairs instead of pews. All three chairs are still produced today.

Kaare Klint continued his professorial work until his death in 1954. He was buried at Tibirke churchyard, but the burial plot has since been closed.

A versatile man

Kaare Klint was, similarly to his father P.V. Jensen Klint, a versatile man, who mastered several scales of design, but it was particularly the smaller scale, furnishing, that became his hallmark. And as mentioned, he designed furniture in collaboration with Carl Petersen as early as 1913 for the art museum in Faaborg. The neoclassic Faaborg chair in particular garnered attention here.

From hospital to museum

Design Museum Denmark (formerly The Museum of Decorative Art) has been housed in one of Copenhagen's finest rococo buildings since 1926, the former Royal Frederiks Hospital in Bredgade. The building was originally erected in the years 1752-57, but it was renovated and refurbished as a museum in the period of 1920-26 by the architects Ivar Bentsen and Kaare Klint. Kaare Klint arranged and designed all the museum's inventory. During this period he taught, worked and lived at the musem and, with the museum as his base, he was mentor to some of the most well-known Danish architects and designers of the 20th century.

Klint and the churches

When his father P.V. Jensen Klint passed away in 1930, Kaare Klint continued his work completing Grundtvig's Church in Bispebjerg, Copenhagen. He spent 10 years on this work, for the church to stand completely finished in September 1940.

He also worked as an architect for the Bethlehem Church in Copenhagen, based on a design created by P.V. Jensen Klint. The church was constructed over the years 1936-37 and was consecrated in 1938. Once again we see how the creative Klint family liked to collaborate on both lamps and architecture, and the desire to create must have been genetic, as Kaare Klint's three sons also took a creative path, becoming architects.

Head of the School of Furniture Design

Kaare Klint's importance as the head of the School of Furniture Design cannot be overstated, however. It was here that he taught the future generations of furniture designers, of which several became part of Danish furniture design's international celebrity during the 1950s. Including Børge Mogensen and Mogens Koch, who became the proponents of functionalism in Denmark. The leading idea was that it was possible to analyse one's way to the correct shape, as the function itself would facilitate the shape. Excess ornamentation and decoration was banned for the self same reason.

Børge Mogensen in particular carried on Kaare Klint's work on the type or the furnishing's fundamental form in his work as the head of FDB's furnishings programme, the congenial aim of which was to create furniture for a broad target audience and at affordable prices.

Democratic furniture vs the desire for perfection

Kaare Klint himself was sympathetic to the notion of democratic furniture, but his need for perfection and insistence on high quality hampered his own work as a democratically-minded designer.

The exclusive, hand crafted furnishings in Cuban mahogany were never intended for the wider public. But as Kaare Klint's lamps for Le Klint demonstrate, he mastered both more humble materials and the sculptural idiom, as the Lantern, for example, not only functionally shades the light, but also does so in an innovative, aesthetically pleasing way.

The Lantern eminently combines the technical aspects of shading the light with the artistic aspects of innovative design.

The Klint brothers shared job assignments.

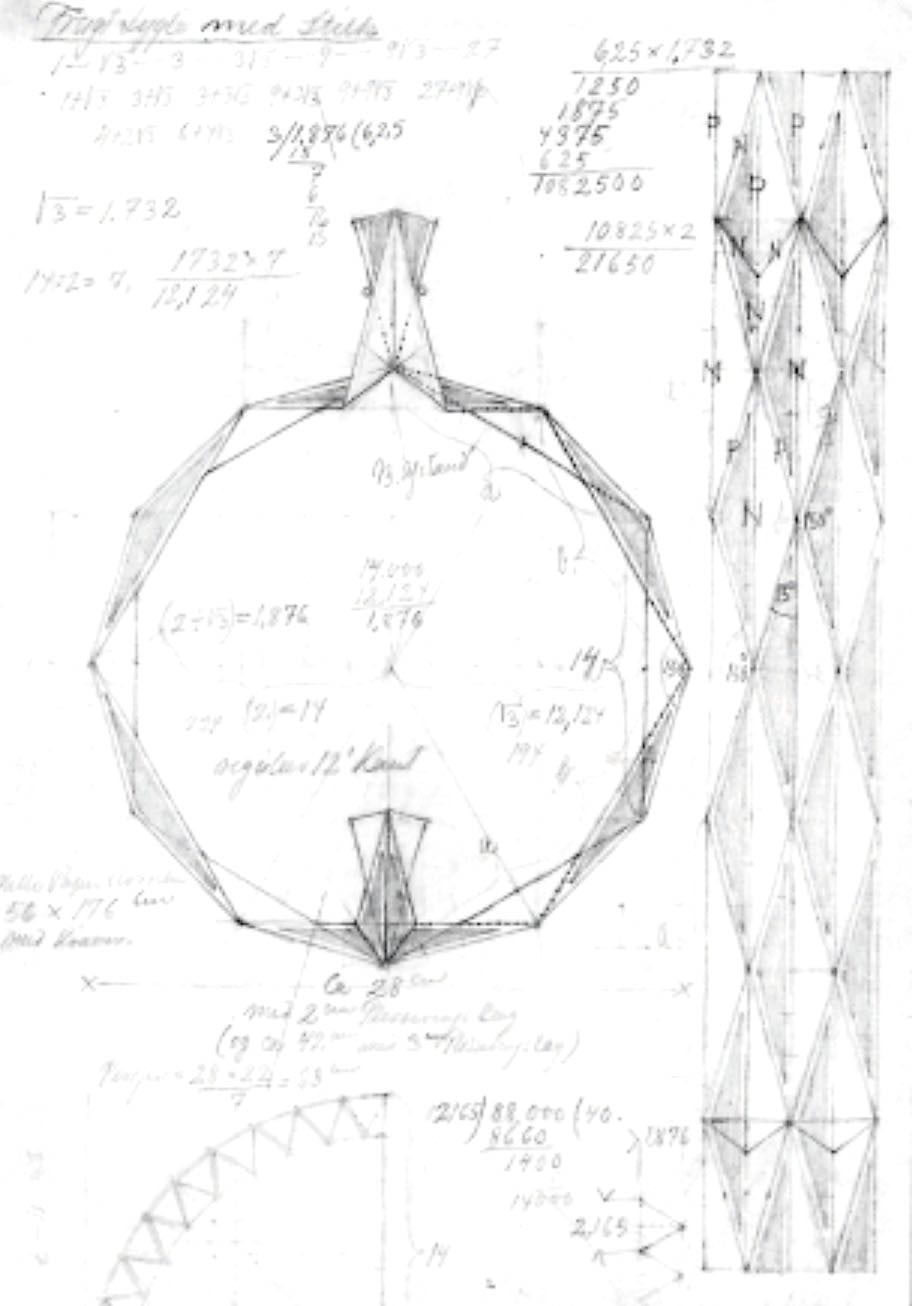

While the older brother Tage Klint primarily took care of the development of the technical principles behind the lampshades, Kaare Klint's speciality was the artistic work, such as printed matters, exhibitions and not least lamps and solid geometric constructions, which his pendant, the Lantern, is a good example of. He also designed the company logo, which was used in the first catalogue in October 1943.

In the preface to the catalogue, he wrote:

''When, or where, on earth the idea of folding pleated paper across the longitudinal originated, I cannot say. I will thus only speak briefly of my first encounter with the small, graceful paper fold and its further development in this country.

It must have been near the turn of the century and I was probably about 10-12 years old. My father had followed the Skovsgaard brother's and Bindesbøll's example and had various ceramic works done at Eifrig in Valby, among other things a foot for a petroleum lamp, and we now needed to shape a distinctive pleated screen that fit the foot. I remember that it was in the evening, and that Father's friend, ship's captain Jeppe Hagedorn, who was visiting, was also tasked with the attempt at shaping a perpendicular collar on the pleated screen.

The collar needed to keep the screen sufficiently far away from the glass of the lantern while still concealing its mouth. That night, the solution was found independently of all other results, and to the joy of the entire family it was the captain who first came across it. We later taught others the trick, and I remember how brilliantly my friend, the architect H.H. Koch, worked the technique, so that full, faceted spheres were produced.

Time after time we addressed the problem, indeed I was even so bold as to use pleated lamps as lighting fixtures in a church. But my brother was the most energetic, initially for his own use, but later as a handicraft, an evening pastime, resulting in presents for friends.

The screens would unfold like sea anemones in his hands. The technique developed and he figured out how to shape the shade's collar in such a way that the shade could be secured to a normal lamp gallery through its own elasticity alone, without any need for a frame.

Through friends of friends, the demand for the Klint lampshades was so great that his daughter, Le Klint, and thus the third generation, took over the production. This turned into a manufacturing process, if a modest one. A patent was taken on the fixing of the shade, and an ingenious machine was created, which eased the manual work.

Gunnar Biilmann Petersen and I helped in the design of a lamp foot, and Mogens Koch, who was in charge of curating and arranging the exhibition of "Danish Artware" in Stockholm in 1942, asked to bring the shades there, and designed a lantern himself, to be hung in the silver corridor.

At the exhibition in Stockholm, and its later showing in Copenhagen, the interest for the lampshades was so great that my brother's daughter Le Klint had the boldness to open a small shop in Copenhagen.

This development, from an inherited design through handicraft to commercial production, is not without tradition in Danish business history.''

Kaare Klint, October 1943 – preface to the first printed catalogue.

Inventory for the shop in Copenhagen

As mentioned earlier, a shop was opened in Copenhagen as early as in 1943 in which Le Klint were displayed and, of course, sold. The shop was fitted by Kaare Klint with shop furnishings in Oregon pine with wicker doors. The original fittings still exist, and are stored at the factory in Odense. The shop walls were papered with Gunnar Biilmann Petersen's flowery "rose paper" in a blue hue, which provided a counter to the simple, white, pleated lamps. The lamp fixtures were designed by Mogens Koch. It was Tage Klint's daughter, Lise Le Charlotte Klint, who was the first manager of the shop.

Kaare Klint's ”Lantern”, Model 101, 1944.

Kaare Klint designed several fine lamps for Le Klint, of which several play a central part in the collection today. The Lantern is one of the most exciting pleated lamps from Le Klint. Even though it is well on in years, it is still among the best selling lamps.

The lamp is fascinating due to its unification of craftmanship, technique and design. It is almost unbelievable that a rectangular piece of paper can be folded into a three dimensional ball with such a beautiful and complicated structure. The lamp harks all the way back to the Chinese paper lamps, but is still its own thing by virtue of the use of the cross-pleating.

The entire experience has meaning

The packaging for the Lantern was designed by Kaare Klint himself, and shows that he was aware of the overall product experience, and wanted to shape the full visual impression.

Jens Otto Krag presents Le Klint with an award

The Lantern has become synonymous in many ways with the fine folded creations, and Le Klint was presented with an award for the lamp as early as 1948. This happened at the fair in Fredericia, where the award was presented by the then trade minister, later prime minister, Jens Otto Krag.

Two positions in one lamp

Kaare Klints ”Kiplampe” (Model 306, 1945)

Kaare Klint not only designed lampshades, but also entire lamps, such as the Model 306 in brass. The classic, warm and glowing "ship's material", brass, works well with the simple pleated lampshade and jointly create a lamp that is equally at home with furnishings using light Danish wooden furniture as it is with a more upholstered, dark, English style.

The feature of the Kiplamp is that it can be tilted or tipped so the light can be directed to where you want it. The lamp has a turning mechanism that allows it to be locked into the two different positions. A functional detail that wasn't common in lamps in the 1940s.